Armenian and Turkish Female Photographers Present Life on Both Sides of the Armenian-Turkish Border

''The New York Times'' has published an article about two female photographers - one Armenian, one Turkish - worked together to document life on both sides of the border, focusing on Armenians living in hiding.

In a handful of villages along the Turkish side of the border with Armenia, neighbors reported a strange occurrence in 2015. Like an apparition, an unlikely pair of women - Anahit Hayrapetyan, an Armenian Christian, and Serra Akcan, a Muslim from Turkey, traveled through the region without men but with cameras, dredging up uncomfortable century-old secrets. The women were searching for "hidden Armenians," whose Christian ancestors survived during the Armenian Genocide, in which nearly 1.5 million Armenians died.

Heranush, an Armenian woman who converted to Islam, at her home where she lives with her children and grandchildren on the hills of Sasun. 2015.CreditSerra Akcan/NarPhotos

These hidden Armenians whom the photographers sought are descendants of survivors, who were mostly women and children taken in by local Kurdish, Turkish and Arab families, and converted to Islam. In some of the more remote villages in Turkey that Ms. Hayrapetyan and Ms. Akcan visited, the ethnic and religious background of these Armenians were concealed out of fear of reprisal from their neighbors. Parents rarely informed children of their Armenian heritage, with many even avoiding the spoken language so children would not pick it up and discover their ancestry.

Ms. Akcan and Ms. Hayrapetyan met in 2006 when they participated in a project between Armenian and Turkish photographers and found that they had much in common. As two female photographers trying to work in patriarchal societies, they became close friends and often leaned on each other for emotional support in their careers.

Local residents in the village of Gomk, in Sasun. Their family is one of the few in Sasun who are still Christian. 2015.CreditAnahit Hayrapetyan/4Plus

In 2009, they decided to work together to document Armenian and Turkish life on both sides of the border, and over the next eight years photographed in the villages and towns along it. At times, Ms. Hayrapetyan carried the youngest of her three children with her.

Though the presence of an Armenian woman on the Turkish side of the border, or a Turkish woman on the Armenian side created difficulties for the photographers, Ms. Akcan said, it was important that they work together.

"We are doing this project because we want to change the single most accepted thing in Armenia and Turkey - that the Armenian and Turkish people are enemies," she said. "So by working together, people start to see that we can be friends - that we can be sisters."

When they started the project about life on both sides of the border they did not know much about the Armenians living in hiding in the Kurdish and Arab villages on the Turkish side, but as they worked they began to hear more about them. So in 2015, Ms. Akcan and Ms. Hayrapetyan turned to finding, interviewing and photographing them.

Images of the Virgin Mary at a sanctum near the Armenian-Turkish border in Anipemza. 2017.CreditSerra Akcan/NarPhotos

Their experiences varied, often village by village. In Kurdish areas it was often easier for the Armenians to talk, Ms. Hayrapetyan said, because the Kurdish people "are going through their own difficult times with the government," and "facing the past, saying that they had a role in the genocide too, and apologizing."

The two wives of a Muslim Armenian man whose father was a survivor of the genocide. The woman on the left is Armenian, and the woman on the right is Arab. Turkey, 2015.CreditAnahit Hayrapetyan/4Plus

Many of the hidden Armenians said they did not know of their background until recently. One man described to them secretly following his grandmother after she said she was going to pick herbs in nearby hills. He discovered her praying in the ruins of an Armenian Christian church in a language he did not understand.

An Armenian woman walks to her house up in the Chengili village of Mush, which is populated mostly by Zaza Kurds. There were around 75,000 Armenians who had lived in Mush and surrounding villages until 1914. Now, the majority of the population consists of Turkish and Kurdish people. 2015.CreditSerra Akcan/NarPhotos

It was a story with particular resonance for Ms. Akcan, because when she was 30 she learned she had a secret connection to the genocide, which her father never told her. Her father’s grandmother was an Armenian, and was discovered hiding in a family garden in eastern Turkey in 1915 or 1916 when she was a teenager. She was taken in by the family and converted to Islam, later falling in love and marrying the oldest son. A few years later, Ms. Akcan’s grandfather was born.

A Muslim Kurdish woman stands in the doorway of her tondir, where bread is baked. The tondir was built using the stones of the old Surb Karapet Monastery of Mush, which was considered an important site before it was burned and pillaged during the genocide. 2015.CreditAnahit Hayrapetyan/4Plus

-

17:08

17:08The regular session of the Anti-corruption Policy Council takes place in Jermuk

-

15:05

15:05The Prime Minister sends congratulatory messages to the supreme leader of Iran and the President of Iran

-

11:11

11:11Armenia sends earthquake aid to Turkey

-

10:43

10:43Commemoration of the Pontiff St. Sahak Partev

-

09:16

09:16Some roads are closed and difficult to pass in Armenia

-

19:55

19:55Phone conversation of the Foreign Minister of Armenia with the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for European and Eurasian Affairs

-

18:30

18:30Prime Minister Pashinyan and President Khachaturyan meet

-

18:20

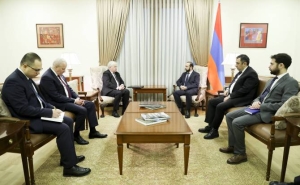

18:20Ararat Mirzoyan with Co-Chairman of the OSCE Minsk Group of France Brice Roquefeuil

-

17:01

17:01Humans could land on Mars within 10 years, Musk predicts

-

16:45

16:45France, US urge 'immediate' end to Nagorno Karabakh blockade

-

16:01

16:01Blockaded Nagorno Karabakh launches fundraiser to support quake-hit Syria

-

15:59

15:59Earthquake death toll in Turkey rises to 18,342

-

15:43

15:43Ararat Mirzoyan Held a Telephone Conversation with Sergey Lavrov

-

15:06

15:06French president rules out fighter jet supplies to Ukraine in near future

-

14:47

14:475 Day Weather Forecast in Armenia

-

14:44

14:44President Vahagn Khachaturyan wrote a note in the book of condolences opened in the Embassy of Syria in Armenia

-

14:20

14:20Azerbaijan’s provocations impede establishment of peace and stability – Armenian FM tells Russian Co-Chair of OSCE MG

-

12:57

12:57France representation to OSCE: Paris calls on Azerbaijan to restore freedom of movement through Lachin corridor

-

11:40

11:40Command of Kosovo forces highly appreciated preparation of Armenian peacekeepers

-

10:16

10:16The United States withdrew from sanctions against Syria for six months the provision of assistance after the earthquake

day

week

month

Humidity: 17%

Wind: 3.6 km/h